“The Black Beach”

“Jim Crow” in Charleston

Charleston, like many southern cities, was segregated during the Jim Crow era and beyond. As Cleveland Sellers writes:

“Segregation, the residential, political, and social isolation of African Americans, was accomplished in South Carolina by a long and varying effort in the aftermath of slavery. The de facto, or socially based, segregation of the races was channeled in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries into a rigid legal, or de jure, system that effectively enforced the second-class citizenship of African Americans. As all-encompassing as the system of ‘Jim Crow’ came to be in South Carolina, it was constructed through a slow and halting process, which black Carolinians contested at every turn.”

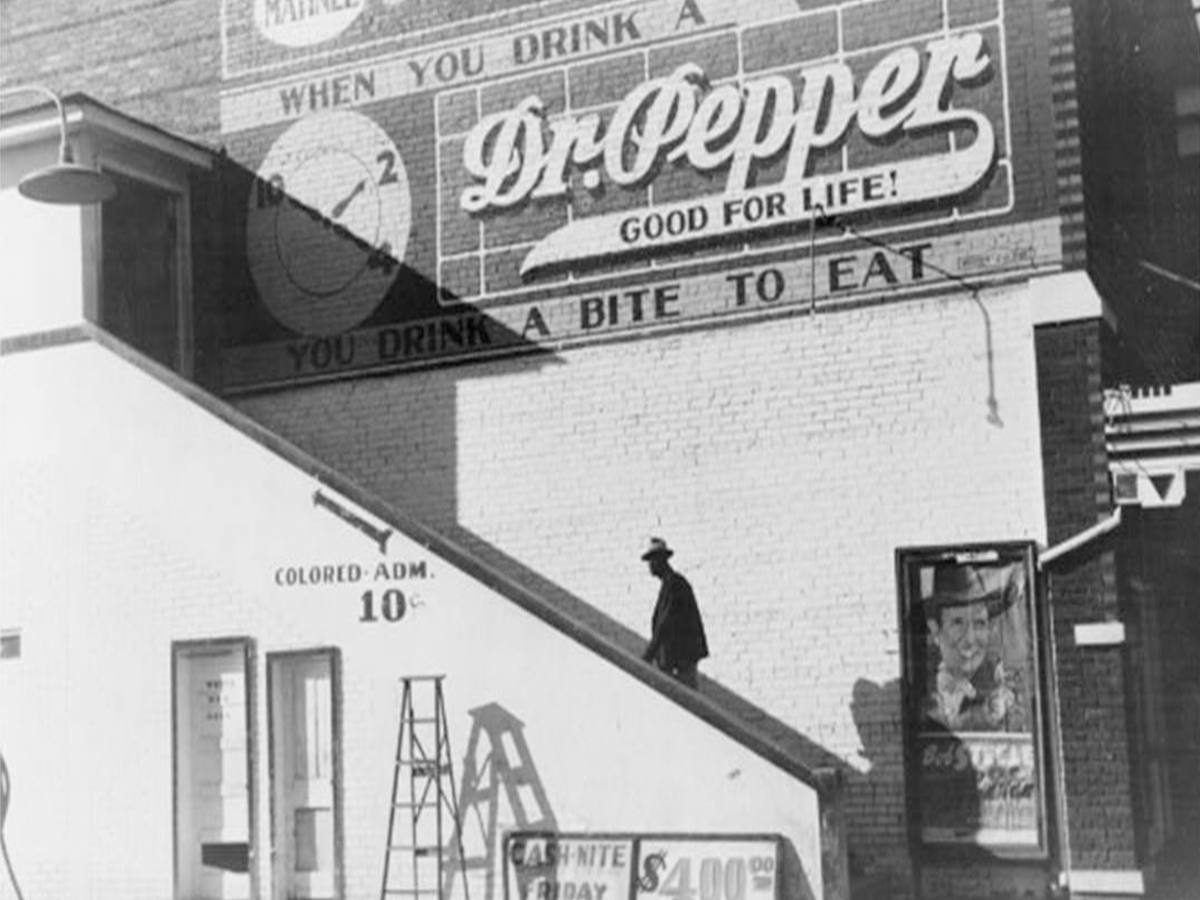

Even after barriers such as public school segregation were legally breached through Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, racial attitudes and social practices in Charleston persisted and these would not be changed simply through legislation. These prevailing attitudes about segregation permeated every aspect of society, from bathrooms, water fountains, schools, transportation, shops and other businesses.

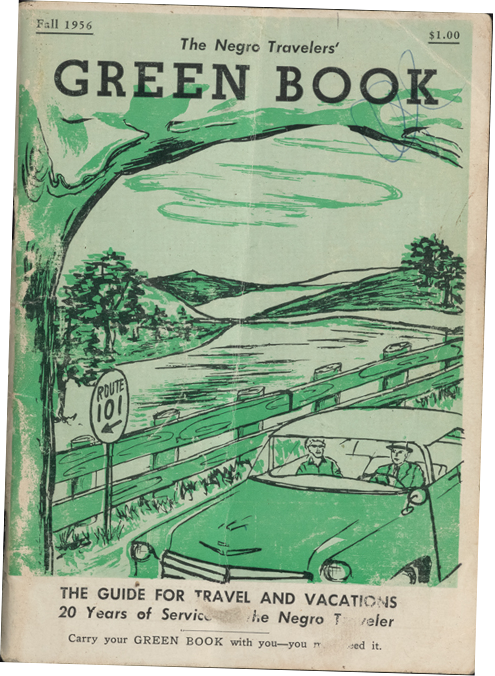

Besides these segregated aspects of everyday life, for many years black Charlestonians had limited or no access to local museums, libraries, theaters, parks, swimming pools, or beaches. When it came to travel, recreation, and entertainment, they had few options; however, African American businessmen and entrepreneurs increasingly created separate black restaurants, hotels, entertainment and music venues. The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, published from 1936 – 1964 by Victor H. Green was a guide book that provided tips and suggestions on how African American tourists and motorists could find these “safe” businesses.

“Black Beaches”

Photograph of unidentified woman seated in Atlantic Beach, South Carolina. Photo courtesy of Bill “Cubby” Wilder.

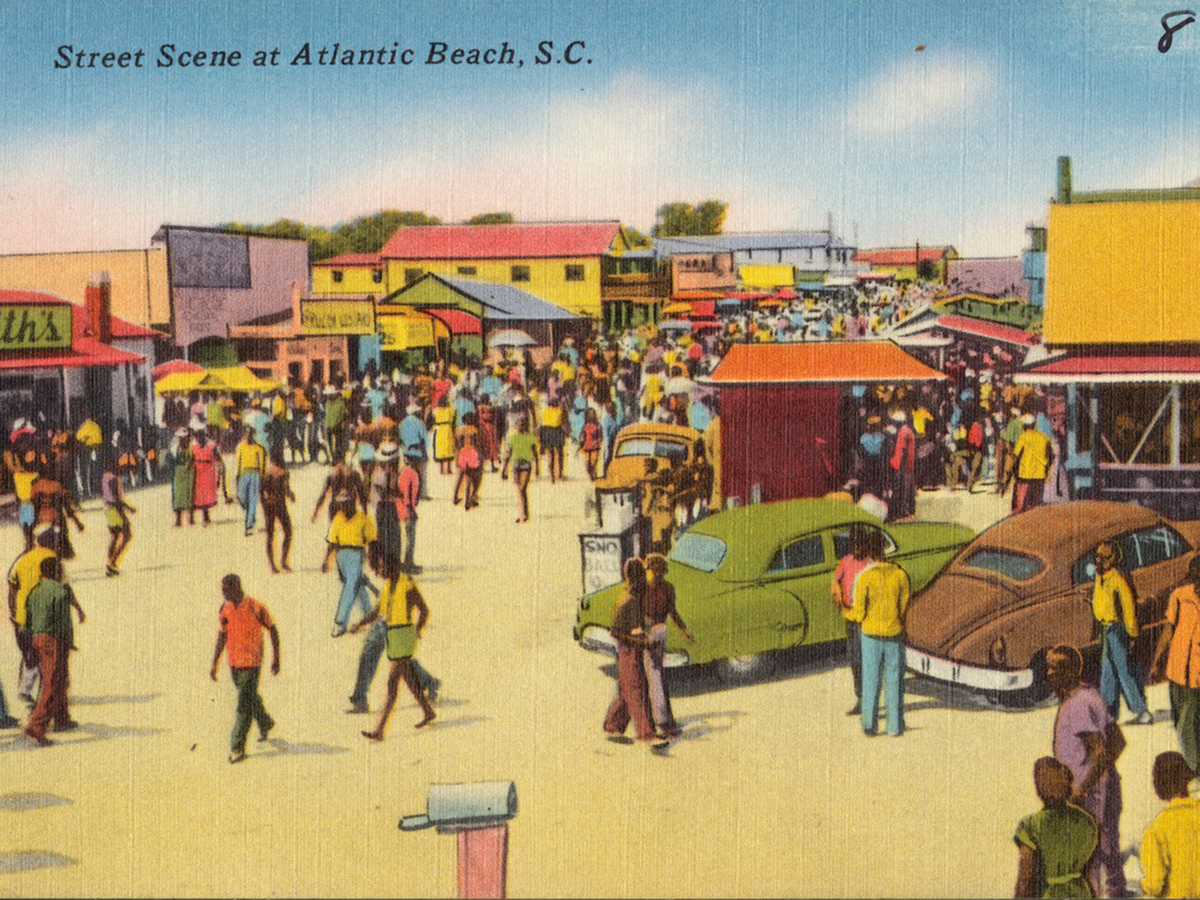

One place along the South Carolina coast featured in the Green Book was Atlantic Beach, developed in 1934 by George W. Tyson, who purchased several tracts of oceanfront property near what is today North Myrtle Beach. Atlantic Beach became known as the Black Pearl and thrived in the 1940s and 50s. Entertainers such as Ray Charles, James Brown, the Drifters, Billie Holiday, and Otis Redding played in the nightclubs of Atlantic Beach after they played for white audiences in nearby clubs. To get to Atlantic Beach, black Charlestonians had to travel about 100 miles to the north, over the old Cooper River Bridge, which typically required an all-day excursion by bus. Even so, beachgoers were always made aware of racial attitudes and segregation as white owners on either side of Atlantic Beach designated their property lines with ropes extending into the surf and signs warning black beachgoers to stay on their side.

The white owners of beaches around Charleston were even more explicit in keeping African Americans out. For the residents of Sol Legare Island, the popular Folly Beach was located nearby, across the marsh and to the south of the Mosquito Beach property but like all public beaches in Charleston at that time, it was only open to the white population. Sol Legare residents generally only went to Folly Beach to find employment as housekeepers, restaurant workers, and custodians. Russell C. Roper worked there and remembered that it was critical “to leave Folly Beach at a certain time” to catch the last bus, to avoid the dangers of walking on the side of the road at night. There are numerous stories of how young black men “testing the waters” of Folly Beach would return to their homes, beaten and bloodied. The tradition of racial segregation at Folly Beach persisted into the 1960s and early 70s.

Mosquito Beach

There was a place nearby, however, that became a recreational oasis created by and for local African Americans. After the closure of the oyster factory at the site, nearby residents and former factory workers continued to gather along the marsh on Kings Flats Creek to catch cooler breezes while they visited with one another and enjoyed local seafood. This area came to be known as “Mosquito Beach,” fittingly named for the bugs that followed people to the marshy edge of the creek.

In the spring of 1953 a boardwalk pavilion was opened by Andrew “Apple” Jackson Wilder. Restaurants, stores, music clubs, and a hotel known as the Pine Tree Hotel (built 1963) followed, and this “beach” attracted people from all over the Lowcountry and beyond. As a nearby resident and (then) president of the group Concerned Citizens of Sol Legare, Susan Chavis, wrote in 2015, the intent of Mosquito Beach “was to give African Americans a place to enjoy themselves by visiting with friends, listening to music, and dancing, enjoying freshly prepared seafood and ‘soul food’ and flirting and finding romance. Here, people could put aside the pressures and negativity associated with racial inequality and simply enjoy life.”

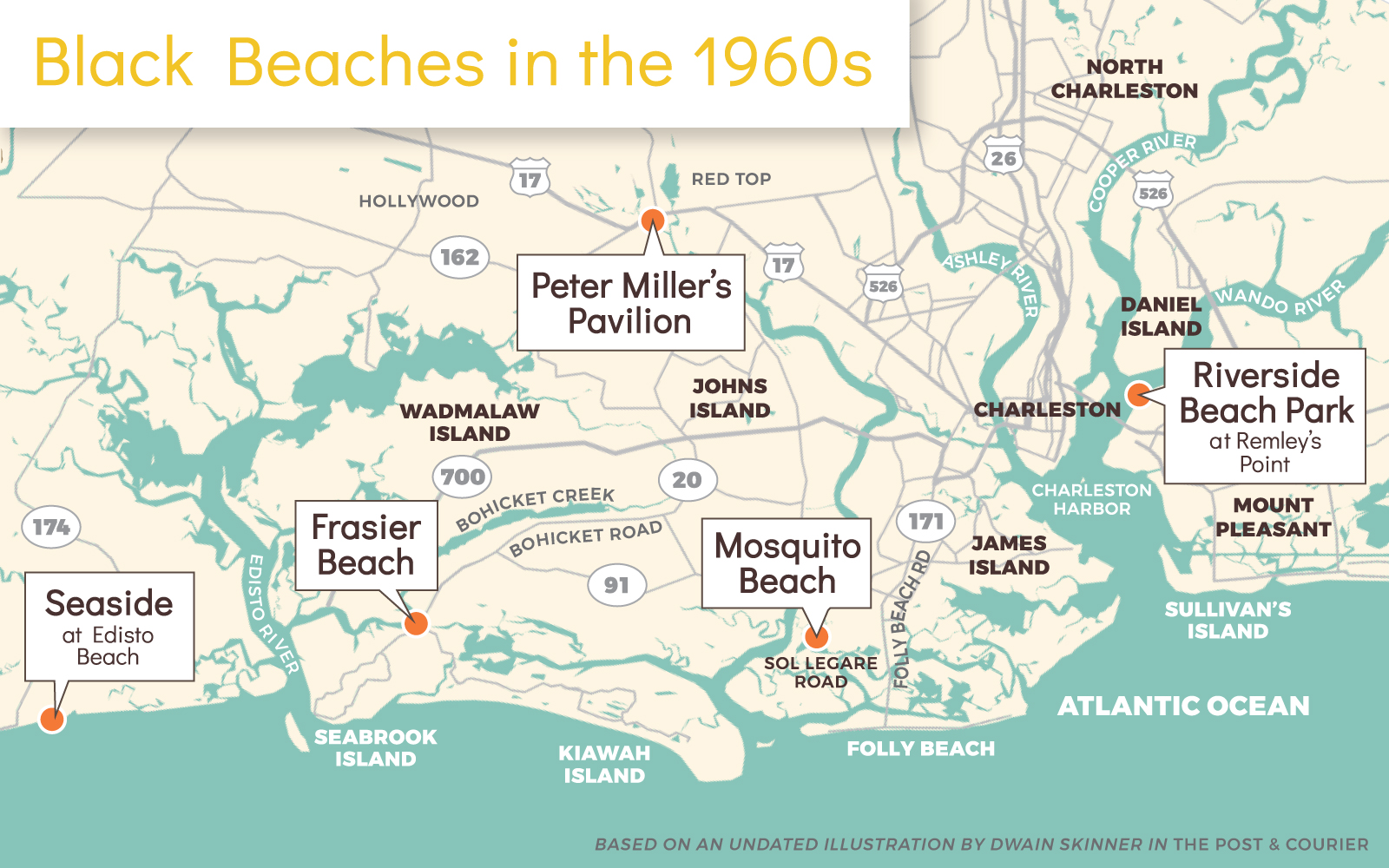

In the mid-20th century, Mosquito Beach was one of only six “black beaches” accessible to the African-American community around the Charleston region. In addition to Mosquito Beach, these other gathering and swimming spots included Seaside Beach on Edisto Island, Frasier Beach on Johns Island, Peter Miller’s Pavilion along Wallace Creek, and Riverside Beach along the Cooper River in Mount Pleasant. Mosquito Beach is a rare survival as most of the others either lost buildings due to natural disasters, neglect, or as historian Andrew Kahrl explains, fell “prey to developers in search of property…and skyrocketing property taxes that accompany the rise of vacationing and tourism along the coast.”

Mosquito Beach was the only gathering place for black citizens to socialize on James Island prior to the mid-1960s and it is one of the last recreation areas of its kind that is still active and largely intact.

“…it was critical ‘to leave Folly Beach at a certain time’ to catch the last bus, to avoid the dangers of walking on the side of the road at night.”

Desegregation

Activity at Mosquito Beach began to dwindle following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Decades after the 1964 act, the Post & Courier reflected that “black-owned businesses that thrived around beaches gradually died after integration.”

New opportunities for black citizens also resulted in the slow decline of activity on the property, as many younger residents left Sol Legare Island to attend college, start employment, or experience life in another state.

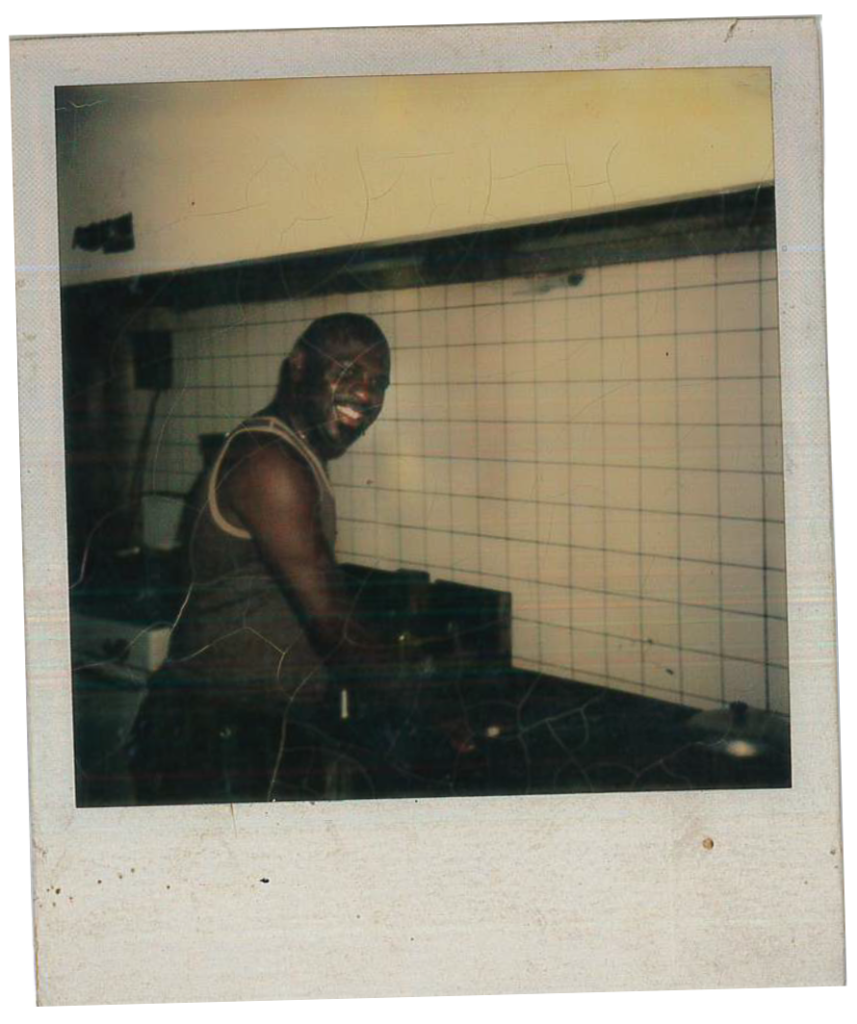

Despite this common migration, two new businesses were started on Mosquito Beach: D&F (formerly Nucka and Manchi’s) and the Lakehouse Club restaurant specializing in seafood. Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, Mosquito Beach continued to serve as a gathering place for the residents of James Island, yet it did not regain the popularity it had in the 1950s and early 1960s.

In the early 1990s, the Mosquito Beach Business Association set out to “recapture and revitalize” the area’s heritage, to portray Mosquito Beach in a positive image and “as a rich cultural experience for everyone.” But in the decade that followed, Mosquito Beach continued to have a reputation for violence and crime. Yvonne Rogers, vice president of the Mosquito Beach Business Association, also told the newspaper that they were prepared to “fight like the devil” to save Mosquito Beach.

Today, three music and food establishments remain: Island Breeze (located in the former Lakehouse Club), D&F’s and the Suga Shack (located in the former Jack Walker’s Club).

Author Eugene Frazier in his book A History of James Island Slave Descendants & Plantation Owners outlines the importance of exposing today’s patrons of Mosquito Beach to the strip’s history:

For many African Americans, it is hard to imagine how far this island has come. It has left them with a legacy of both the joy and the pain of living in a time and place wrought with hardship but somehow still intermingled with the happiness that comes from a community built on family, love, strength and honor. It is a legacy that is impossible to forget.

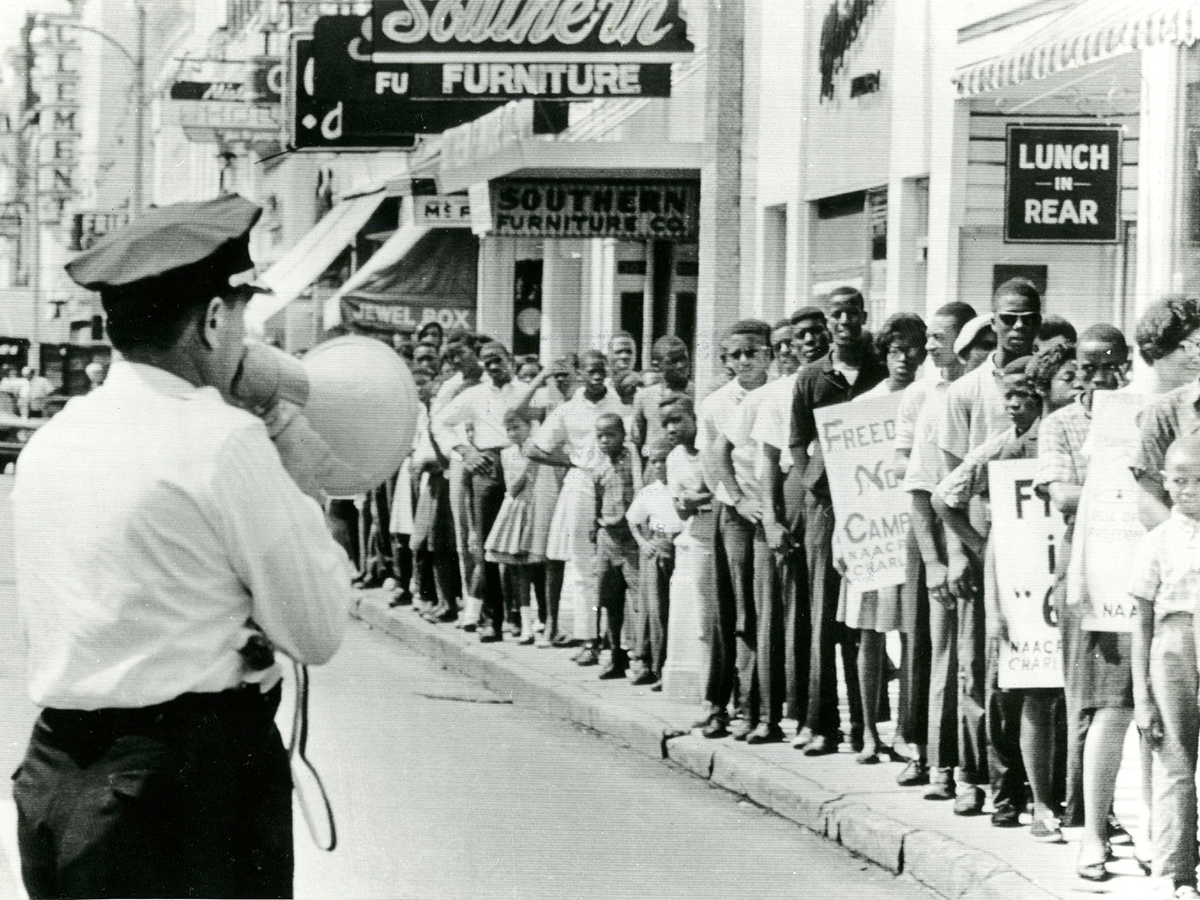

1963 photograph, Civil Rights Photography Folder, from the collection the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, Charleston, SC

This material was produced with assistance from the African American Civil Rights grant program, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.

This material was produced with assistance from the African American Civil Rights grant program, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.