Buildings of Mosquito Beach

Mosquito Beach Buildings

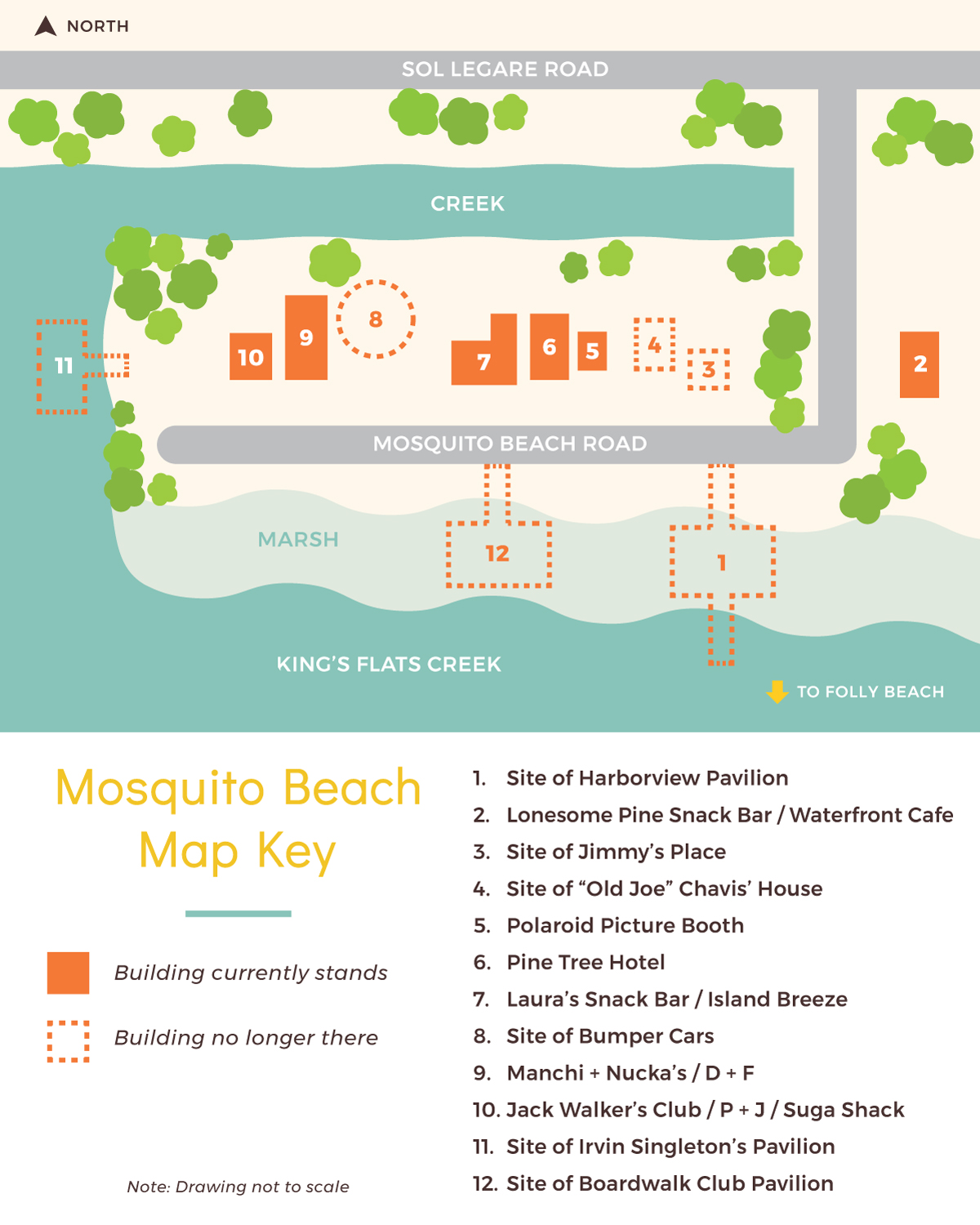

As the sun sets over the Kings Flats, it creates a magnificent and colorful view of the marsh on a high tide. In the 1950s and 60s, huge crowds of young and old flocked to Mosquito Beach to mix and mingle, leaving aside the restrictions of Jim Crow segregation. Single girls and young fellows would grab a Coke or a beer and “slow drag” to Brooke Benton’s “Think Twice Before You Answer,” or Sam Cooke’s “Darling You Send Me.” Chevys and Fords lined the street. The smell of fried chicken, fresh farm grown vegetable dishes and in-season seafood would set mouths to watering. The buildings and boardwalks of Mosquito Beach were the backdrop for a million different meals, dances, conversations and budding romances on long, lazy summer days and nights.

The buildings of Historic Mosquito Beach are located primarily along the north side of Mosquito Beach Road and face the marsh and King Flats Creek. Today, they include a hotel, and several clubs, and restaurants. The remnants of three boardwalk/pavilions remain in the marsh, their wooden pilings visible at low tide.

Explore Mosquito Beach From Above

Thanks to Dr. Jon Marcoux for providing this interactive high-resolution ArcGIS map of Mosquito Beach. Use the + icon to zoom in and drag to see different areas more closely (and compare to the site map above!).

Mosquito Beach Building Descriptions

Site of the Harborview Pavilion (Built 1953, Destroyed 1959)

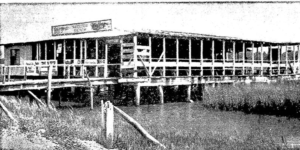

The Harborview Pavillion, photographed in 1959 with members of Wilder, Walker, Lafayette Richardson and Chavis families, courtesy of Bill “Cubby” Wilder

This pavilion was the first big commercial draw to Mosquito Beach. It was located directly across from a popular store owned by “Old Joe” Chavis (b. 1908). An early 1950s photograph depicts the pavilion as a single story, open-air structure on wooden piers with a hipped roof and exposed rafters. The same photo shows promotional signs, including one for Ballantine Ale hanging on the pavilion along with benches on the pavilion’s west side, while the east side, not pictured, included a bedroom for workers, bar and kitchen with a back deck. Lucille Wilder Washington later told the Post & Courier that she worked as a cook in this pavilion, often serving ham, franks, red rice and chicken to patrons.

The pavilion was destroyed by Hurricane Gracie in 1959 and was never rebuilt in that location. All that remains are the pavilion’s foundation piers, which are present in the marshes of King Flats Creek at both low and high tide.

The earliest Mosquito Beach memory of Cassandra Singleton Roper was of the Harborview Club shortly after it opened. She remembered walking “across the creek” that separated Mosquito Beach from the rest of Sol Legare Island as an eight-year-old to dance “on Sundays.” Ms. Roper was often accompanied by her friends, who collected money from the patrons in the pavilion as she danced to the “piccolo,” a name the children called the jukebox. Dancing at the pavilion was most often the impetus to behave as a child – many residents of Sol Legare Island remember being allowed to visit Mosquito Beach as a child only on Sundays if they obediently attended school and church, as well as completed their weekly chores.

Lonesome Pine Snack Bar / Waterfront Cafe

Charles and Willameania Richardson built a small snack bar here on the Gilliard property in 1962. The Lonesome Pine operated from 1962-1965. The open deck was used as a dance floor, a dining area and a place for patrons to mix and mingle. The deck overlooked incredible views of the marsh and creek. According to family members, Charles Richardson wasn’t able to get electricity so he worked a deal with his closest neighbor Joe “King Pin” Chavis, who got his electricity from Andrew “Apple” Wilder. “Every time Charles and Willameania would get a crowd the lights would go out. According to King Pin, ‘the circuit got overheated.’”

After the Lonesome Pine closed down, a fire destroyed the building. The current building was constructed nearby in 1972 as a club by Hezekiah Ladson, Josiah Smalls and Thomas Greene. The H.J. and T. Club was known as a favorite spot of the older crowd and it operated until 1982. Ernie’s Cove was operated by Ernest Gilliard until 1989 when he was joined by the Gilliard family to assist with management after Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Waterfront Cafe took ownership in 2001, known for its Gullah dishes, it also played host to celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain.

Site of Jimmy’s Place

Site of Joe Chavis’s House & Store

Even after the oyster factory closed down in the early 1930s, the area locally coined as “The Factory,” continued to serve as an informal gathering place for the surrounding community. Notably, Joe Chavis’s business on the Lafayette property near the northeast bend of what is today known as Mosquito Beach Road, was established by the early 1930s. It was meant to cater to the former factory workers who continued to meet there after the factory’s closure. Joe Chavis, also known as “Little Bubba” and later as“King Pin,” operated the Seaside Grill on the ground floor of his two story wood house, with living quarters above. Patrons remember a “jukebox, pool table, and menu of fresh steamed clams and crabs.” Joe Chavis’ store, which he operated until the mid 1980s was ultimately destroyed in 1984 by a fire, which also took the life of his wife Mittie, then 73-years-old and blind.

Polaroid Picture Studio

This small building once housed a picture studio where patrons of Mosquito Beach could have their polaroid picture taken as a memento of their visit. Russell Roper talks about owning and operating the studio in his oral history interview. The small studio was added onto later and used as a snack bar.

Pine Tree Hotel (Built 1962-64)

South (primary) facade of the Pine Tree Hotel, photo taken September 2018 by Historic Charleston Foundation

The Pine Tree Hotel is a two-story frame building constructed between 1962-64. It is a rare survival of an African American hotel and it reinforces the notion that visitors to Mosquito Beach were not just “locals” but travelled here from a wide area. The hotel provided needed accommodation for visitors as prior to this many people who traveled to Mosquito Beach slept in cars. The Pine Tree Hotel was constructed by owners Laura and Andrew “Apple” Wilder (1922-1984). The hotel had fourteen rooms and guests shared a common kitchen and bathroom. Laura Wilder, in addition to cooking for the Boardwalk Club, oversaw the maintenance of the hotel.

The Pine Tree Hotel closed for repairs in 1989 after damage sustained by Hurricane Hugo but has never reopened. Later alterations such as the removal of the original porch across the front of the building resulted from damages caused by Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Irma in 2017. For many years, owner Bill “Cubby” Wilder has sought to save this historic building built by his uncle even as the poor state of the building has several times prompted building inspectors to order its demolition. The Mosquito Beach community are joined by local preservationists who believe that the history and significance of the hotel warrant its continued preservation.

Laura’s Snack Bar / Island Breeze (Built c. 1962-65 )

Significant interior features include the building’s original plywood apron interior walls, concrete floor, and the open dance floor and stage within the historic core.

Site of the Bumper Cars

Many visitors to Mosquito Beach had fond memories of the bumper car operation that was located between Island Breeze and D&F’s. Starting in 1955, the bumper cars were an attention catcher and attraction, but they only lasted for a handful of years. William “Cubby” Wilder related that during Hurricane Gracie, “the bumper cars got damaged because when we came back down here, the bumper cars were all over…. It was electrical, so it was gone. And then they just move it out, never decide to put one back.”

Manchi and Nucca’s Place / D&F’s

North elevation of D&Fs, looking northeast, photo taken March 2019 by Historic Charleston Foundation

Inside the current structure there is a full-width room that is occupied by a bar and lounge. Significant interior elements include the building’s original wooden bar, concrete floor, wood paneling, and DJ booth. A small open-air porch at the rear was added more recently.

Jack’s Place / P&J Club / Suga Shack

Often referred to as a “piccolo joint,” this was a nightclub frequented by the older Beach patrons. It was originally owned by farmer and fisherman Jack Walker and was also called P&J’s after Jack and his son Perry.

Site of Irvin Singleton’s Pavilion

Irvin Singleton constructed a similar, open-air pavilion with a square footprint in the early 1960s after Hurricane Gracie destroyed much of the Beach. Although not much is known about the appearance of this pavilion, it has been described as almost identical to Apple Wilder’s Harborview Pavilion and Boardwalk Club. The pavilion was also destroyed by Hurricane Hugo in 1989. All that remains are the pavilion’s foundation piers, which are present in the marshes of King Flats Creek at both low and high tide.

Site of the Boardwalk Club

Boardwalk Club, 1964 Post & Courier article “Mosquito Beach is a Popular Retreat for Negro Citizens”

After the destruction of the Harborview Pavilion, “Apple” Wilder constructed a larger open-air dance pavilion west of the previous pavilion’s location on property he purchased in 1959. At the time of the pavilion’s completion in 1963, it had a capacity for 800 people.

In 1989, the pavilion was destroyed by Hurricane Hugo. All that remains are the pavilion’s foundation piers, which are present in the marshes of King Flats Creek at both low and high tide.

“Apple” Wilder designed and built the new Boardwalk Club to resemble the Harborview Pavilion, which was lost during Hurricane Gracie, but increased the scale of the structure to accommodate more people. Wilder and others participated in the moonshine business on Mosquito Beach and it was served at the Boardwalk Club along with other drink options and food.

This material was produced with assistance from the African American Civil Rights grant program, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.

This material was produced with assistance from the African American Civil Rights grant program, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.